The Inner Orchestra of Parts

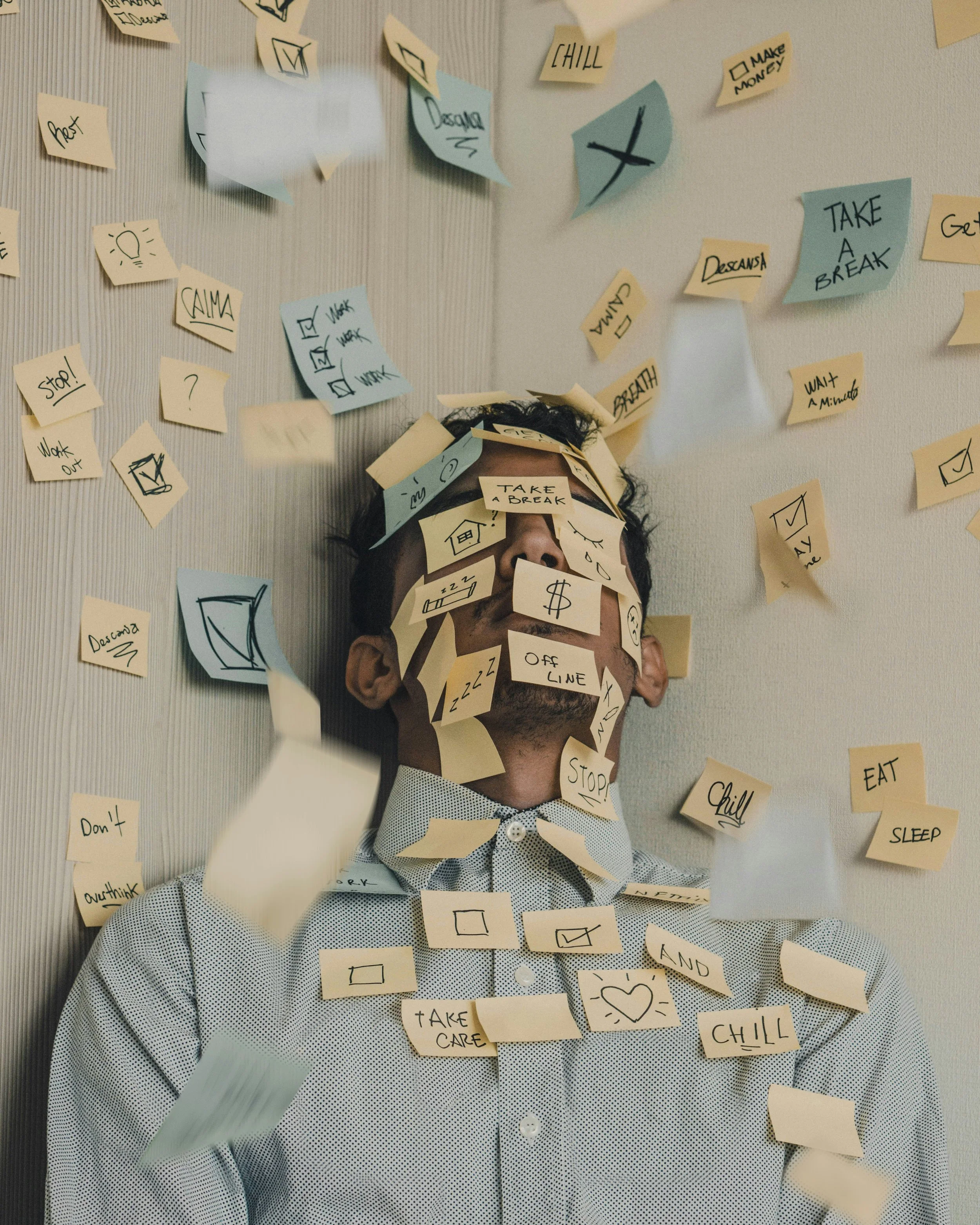

Do you ever have “mixed feelings” or experience several different emotions all at once in response to one pertinent issue or life stressor? In these moments, does it sometimes feel like you’re sitting around a chaotic dining table with all of your most opinionated or eclectic family members talking about controversial topics like politics, social issues, simulation theory, flat-earth rhetoric or what kind of bagel is objectively most delicious? You may have just encountered the cacophony of your various inner parts, or your Internal Family System.

What is IFS or Internal Family Systems?

Developed by Dr. Richard Schwartz, Internal Family Systems, or IFS, is a therapeutic theory and modality centered around the idea that we contain multiple inner parts, all with their own unique perspectives, drives, and motivations. Most often, each part has a different idea of how to support the core Self, or the integrated, balanced, and whole person within every individual.

According to IFS, these inner parts can often be categorized into three common roles:

Exiles, Managers, and Firefighters.

Who are Exiles in IFS?

Exiles are wounded, hurt, or shameful parts that have been exiled from the Internal Family. (In terms of family tropes, think the estranged black sheep of the family...probably goth).

Who are Managers in IFS?

Managers strive to protect and…well, manage…emotions and the environment, and attempt to keep the exiles hidden or banished. (This is heavily eldest daughter-coded or helicopter mom).

Who are Firefighters in IFS?

And firefighters are the cope-ers, inhibiting painful or activated emotions (exiles) by numbing or preventing further pain (i.e. binge-eating, substance use, etc.) (I think of firefighters as the tough brothers or sisters, getting detention for starting a fight with their little sibling’s bully).

While that’s the traditional breakdown of IFS, I personally like to think of the internal family system as an orchestra, where all the inner parts are instruments with their own unique sounds and designated melody lines. The Self is the conductor, directing each musical section to play as one.

It’s giving “serene symphony" when we feel balanced and integrated.

But what’s going on when we don’t feel like we’re at peace inside?

When we experience any sort of thought, feeling, or narrative that sticks out from our daily norm or causes distress, I like to imagine or conceptualize this as one of the orchestral instruments–let’s go with a violin (pun intended)--playing out of tune or much louder than the rest of the instruments or going rouge and deciding it’s time for a solo.

It's our job in therapy to create space for this blaring instrument, to hear its unique melody and point of view, to allow it to play the line of music it intends and examine its tone, melody, or meaning, and maybe tighten or loosen its strings so that it can return to the orchestra, feeling quite literally heard, and thus, a valuable part of the orchestra at large.

For example, perhaps you’ve just ended a turbulent romantic relationship for the purpose of self-preservation after tolerating months of violated boundaries, despite your continual efforts to communicate them. (This is a total hypothetical and bears no resemblance to anything I have personally experienced…okay?) You have many feelings associated with this ending, some of them complicated and even contradictory: You may feel the grief and loss of losing your “best friend.” Perhaps you feel severe disappointment that they couldn’t show up for you as they promised or like you had hoped. Maybe you feel anxiety and doubt, now questioning their motives and intentions during the entirety of the relationship?

Now imagine each one of these feelings associated with an instrument in the internal orchestra: Maybe the grief and loss is a clarinet, the disappointment a French horn, and the doubt and anxiety is a fluttery flute. They all have their own individual melody lines in the music, but they play in harmony, together, led by the conductor-Self to play the melancholy yet triumphant symphony titled “I’m Extremely Sad But I Did the Right Thing For My Own Self–Respect and I’ll be Better for it, in F# Major”.

However, after a few minutes of collective playing, a disturbingly screeching sound pipes up, shriller than the rest of the orchestra. It’s none other than the high-pitched Piccolo, playing louder, higher, and rhythmically slower than the group, whining to be heard. Its mismatched melody or sentiment longs to go back to the relationship and worries if ending it was a huge mistake. And rather than discipline the Piccolo for playing out of turn or excusing it from the orchestra all together, the conductor-Self asks all the other instruments to pause their melodies for a brief moment and to turn their attention to the meager Piccolo to listen to its concerns.

The Piccolo continues its solo that sounds a little like: “I know we’re all playing a triumphant piece about empowerment and making space for the new love we deserve, but I’m really scared that if I don’t go back to that relationship, I’ll never be loved again.” After allowing the Piccolo to express itself, the conductor-Self understands and validates the Piccolo’s fear and invites it to play its line of music in harmonious tone, volume, and rhythm with that of the other instruments in the orchestra. It can now play along with the rest of the orchestra, after its message has been heard and registered.

All instruments are welcome to play together, with their unique sounds and melodies. Just like all emotions, thoughts, and narratives are welcome to share their individual perspectives with us. It’s in the valuing or devaluing of one thought or feeling over another or the compartmentalizing or suppression of these unwanted thoughts or feelings that cause the symphony to play out of tune. When we can listen to and justify all the instruments' sounds and melodies in the orchestra, no matter how different they might sound from each other, we can achieve greater integration, inner peace, and self-acceptance.

If we learn to treat our internal parts with curiosity and acceptance rather than fear or judgment, we can shift from fighting the noise to conducting the music. IFS invites us to honor each emotion—not as a threat or a flaw, but as an instrument, with a unique sound, trying to help in the only way it knows how. With guidance and practice, we can begin to hear not just the dissonance, but the emerging harmony. Over time, our internal symphony becomes less about perfection and more about the relationship: listening, attuning, and allowing every part to belong. Even that shrill piccolo.

If you’d like to learn more about Internal Family Systems or parts work, I suggest reading No Bad Parts by Dr. Richard Schwartz. IFS can be helpful for working through situations we all experience, like a bad breakup, and for more intense situations like childhood trauma and events that cause PTSD.

If you’d like to begin your own journey working through your internal orchestra, feel free to reach out to our Client Care Coordinator today to find a therapist who can help you listen in and learn how to honor and conduct your very own internal family orchestra/system.

Warmly,

Ali Eagle, AMFT